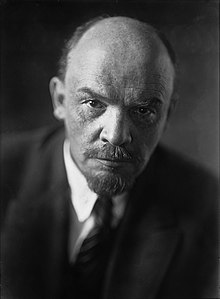

Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924) was a Russian revolutionary, political theorist, and the leader of the Bolshevik Party who played a key role in the 1917 Russian Revolution and the subsequent establishment of the Soviet Union. As the first head of the Soviet state, Lenin laid the ideological foundation for Soviet communism and Marxist-Leninist thought, which would shape the 20th century and influence revolutionary movements worldwide. Lenin's leadership was marked by his relentless drive to overthrow the Russian monarchy, his decisive role in the October Revolution, and the implementation of socialist policies that radically transformed Russia’s political, economic, and social structures.

Birth and Family Background: Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (Lenin) was born on April 22, 1870, in Simbirsk (now Ulyanovsk), Russia, into a moderately well-off family. His father, Ilya Ulyanov, was a government official in the field of public education, and his mother, Maria Alexandrovna, came from an educated, cultured background. Lenin's upbringing was intellectually stimulating, and he excelled in his studies from a young age.

The Execution of His Brother: One of the most formative events in Lenin's early life was the execution of his older brother, Alexander Ulyanov, in 1887. Alexander was a student radical involved in a plot to assassinate Tsar Alexander III. His arrest and subsequent execution for his revolutionary activities deeply affected Lenin, pushing him toward radicalism and shaping his political path.

Education and Introduction to Marxism: After his brother’s execution, Lenin entered Kazan University to study law but was expelled for participating in student protests. Despite this, he continued his studies independently and became interested in the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, particularly Das Kapital. By the early 1890s, Lenin had fully embraced Marxism, seeing it as the key to understanding social and economic inequality and a guide to revolutionary change.

Early Revolutionary Work: In the 1890s, Lenin became increasingly involved in Marxist revolutionary activities. He joined illegal Marxist groups, distributing propaganda and organizing workers. In 1895, he helped found the Union of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class in St. Petersburg, advocating for workers’ rights and spreading revolutionary ideas.

Arrest and Exile in Siberia: In 1897, Lenin was arrested by Tsarist authorities for his revolutionary activities and sentenced to three years of exile in Siberia. During this time, he married Nadezhda Krupskaya, a fellow revolutionary and lifelong collaborator. Lenin continued his political writing during exile, formulating his ideas about the necessity of a revolutionary party to lead the working class.

Adopting the Name Lenin: After his release from exile, Lenin moved to Western Europe to avoid further persecution by the Tsarist regime. It was during this time that he adopted the pseudonym Lenin, possibly derived from the Lena River in Siberia. While in exile, Lenin worked tirelessly to organize revolutionary activity in Russia from abroad, editing the revolutionary newspaper Iskra (The Spark) and writing several key works that laid out his vision for a Marxist revolution.

Split with the Mensheviks: In 1903, the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP) split into two factions: the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, and the Mensheviks, led by Julius Martov. The split was primarily over Lenin's insistence on a small, tightly organized party of professional revolutionaries, whereas the Mensheviks favored a broader, more inclusive party. Lenin's vision for the Bolshevik Party was one of discipline and centralization, where the party leadership would play a decisive role in guiding the revolutionary movement.

Revolution of 1905: Although the 1905 Russian Revolution was ultimately unsuccessful, it was a significant moment in Lenin’s political development. He saw the revolution as proof of the working class’s revolutionary potential, though he also recognized the need for stronger leadership to channel that potential toward a successful overthrow of the autocratic regime. The 1905 uprising was a precursor to the more significant revolution that would follow in 1917.

World War I and the Collapse of Tsarism: The outbreak of World War I in 1914 severely weakened Russia, both economically and politically. The massive loss of life, military defeats, and economic hardship exacerbated discontent with Tsar Nicholas II’s government, leading to widespread strikes, protests, and demands for change. In early 1917, a popular uprising, known as the February Revolution, forced Tsar Nicholas II to abdicate. A Provisional Government was established, but it struggled to address the needs of the Russian people and continued to prosecute the war.

Lenin’s Return to Russia: Lenin, who had been living in exile in Switzerland during the war, saw the February Revolution as an opportunity for the Bolsheviks to seize power. With the help of the Germans (who hoped his return would destabilize Russia), Lenin was smuggled back into Russia in April 1917. Upon his return, he delivered the April Theses, calling for an immediate end to the war, the transfer of land to the peasants, and the establishment of Soviet (workers’) control over the government. His slogan “Peace, Land, and Bread” resonated with the Russian masses.

October Revolution (1917): By the fall of 1917, Lenin and the Bolsheviks were prepared to overthrow the Provisional Government, which had failed to deliver on its promises of land reform and peace. On October 25, 1917 (by the Julian calendar, November 7 in the Gregorian calendar), the Bolsheviks, led by Lenin and Leon Trotsky, launched a coup, seizing control of key government buildings in Petrograd (St. Petersburg). The October Revolution was swift and relatively bloodless, and by the end of the day, the Bolsheviks were in control of the capital.

The Soviet government, with Lenin at its helm, declared the formation of a socialist state and began the process of withdrawing Russia from World War I. The revolution fundamentally changed the political landscape of Russia and laid the groundwork for the establishment of a communist state.

Russian Civil War (1917–1922): After the October Revolution, Lenin faced the challenge of consolidating power in a country deeply divided by political, social, and ethnic tensions. The Russian Civil War broke out between the Bolsheviks (Reds) and a coalition of anti-Bolshevik forces known as the Whites, which included monarchists, liberals, and foreign interventionists. The civil war was brutal, with millions of lives lost due to fighting, famine, and disease.

Under Lenin’s leadership, the Bolsheviks implemented harsh measures to maintain power, including the Red Terror, a campaign of political repression that targeted perceived enemies of the revolution. The Cheka (secret police) was created to eliminate counter-revolutionaries, and many were imprisoned or executed. Despite the violence, Lenin’s government succeeded in defeating the Whites and securing Bolshevik control over Russia.

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (1918): One of Lenin’s first major actions as head of the Soviet government was to fulfill his promise to withdraw Russia from World War I. In 1918, Lenin signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany, which ended Russia’s involvement in the war but at a significant territorial cost. The treaty ceded vast areas of the Russian Empire, including Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic states, to Germany. While the treaty was deeply unpopular, Lenin saw it as a necessary step to preserve the Bolshevik government and focus on internal issues.

War Communism and Economic Crisis: During the civil war, Lenin implemented a policy known as War Communism, which involved the nationalization of industry, the requisitioning of grain from peasants, and centralized control of the economy. While these measures helped the Bolsheviks win the war, they devastated the Russian economy and led to widespread famine and unrest.

New Economic Policy (NEP): In response to the economic crisis and a series of uprisings, Lenin introduced the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921. The NEP represented a retreat from pure socialist policies and allowed for a limited revival of private enterprise, particularly in agriculture and small-scale industry. The NEP helped stabilize the economy and brought some relief to the population, though it was seen as a temporary compromise with capitalist practices.

Marxism-Leninism: Lenin’s theoretical contributions to Marxism, often referred to as Marxism-Leninism, became the official ideology of the Soviet state and later of communist movements around the world. Lenin adapted Marxist theory to fit the conditions of early 20th-century Russia, arguing that a vanguard party of professional revolutionaries was necessary to lead the working class in overthrowing the capitalist system. His belief in the centralization of power, the dictatorship of the proletariat, and the need for violent revolution became foundational principles of communist rule.

Dictatorship of the Proletariat: Lenin believed that after a socialist revolution, a dictatorship of the proletariat was necessary to suppress the former ruling classes and consolidate socialist power. This concept justified the use of repression against political opponents and led to the establishment of a one-party state under Bolshevik control. Lenin’s emphasis on the role of the party and the use of state power to achieve socialist goals would influence later communist leaders, particularly Joseph Stalin.

Death and Succession: Lenin suffered a series of strokes in the early 1920s, which progressively debilitated him. He died on January 21, 1924, at the age of 53. Lenin’s death led to a power struggle within the Soviet leadership, with Joseph Stalin, Leon Trotsky, and others vying for control of the party. Ultimately, Stalin emerged as Lenin’s successor, consolidating power and leading the Soviet Union into a new, even more repressive era.

Founding Father of the Soviet Union: Lenin’s leadership was crucial in the creation of the Soviet Union (established in 1922) and the survival of the Bolshevik regime in the aftermath of the revolution. His vision of a communist state, with centralized control and a vanguard party, shaped the Soviet system and influenced communist movements globally. Lenin remains a revered figure in communist ideology, though his methods of maintaining power, particularly his use of political repression, have been widely debated and criticized.

Controversial Legacy: Lenin’s legacy is deeply controversial. On one hand, he is celebrated as the revolutionary leader who overthrew the oppressive Russian monarchy and established a socialist state. On the other hand, his use of terror, his suppression of political freedoms, and his role in laying the groundwork for Stalin’s dictatorship are viewed as dark aspects of his legacy. While Lenin envisioned a classless, stateless society, his actions created a centralized, authoritarian regime that would become synonymous with political repression.

Influence on Global Communism: Lenin’s ideas and actions had a profound impact on the global communist movement. His theories of revolutionary leadership and state socialism influenced communist revolutions in China, Cuba, Vietnam, and many other countries throughout the 20th century. Leninism, as distinct from Marxism, emphasized the role of the revolutionary party and the necessity of seizing state power to achieve socialism, ideas that resonated with revolutionary movements worldwide.

Vladimir Lenin was one of the most significant and transformative political figures of the 20th century. His role in leading the 1917 Russian Revolution, his establishment of the Soviet state, and his contributions to Marxist theory have left a lasting legacy on both Russian and global history. Lenin’s vision of a socialist society, and the methods he used to achieve it, continue to be the subject of intense debate, but his impact on the course of world events is undeniable. His leadership during a time of immense political upheaval helped shape the Soviet Union and inspired revolutionary movements around the world, though the human cost of his policies remains a point of profound historical reflection.

We use cookies

We use cookies and other tracking technologies to improve your browsing experience on our website, to show you personalized content and targeted ads, to analyze our website traffic, and to understand where our visitors are coming from. Privacy Policy.